The Cabin in the Woods is a 2012 American horror film which can be categorised as a deconstructionist horror film, as it plays with the generic conventions of horror films and engages the audience in an ideological discourse about the audience need for and response to the genre.

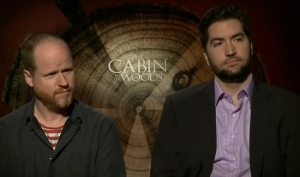

Drew Goddard and Joss Whedon, who directed, produced and co-wrote the film, have described it as an attempt to revitalise the slasher cycle and as a critical satire on the popularity of ‘gore porn’.

The film was shot in Canada (often a cheaper alternative than shooting in the US) in 2009. The estimated budget for the film is $30 million. Principal photography lasted approximately 8 weeks.

Industry – Business and Release

The film was initially scheduled for release in February 2010, with this date being pushed back until January 2011 in order for the film to be converted into 3D. However, MGM, the studio behind the film filed for bankruptcy before the film’s release and so the film’s released. Following new ownership at MGM, the distribution rights for The Cabin in the Woods were sold to Lions Gate Entertainment. Despite hopes for a release in time for Halloween in 2011, Lions Gate eventually announced that the film would be released in April 2012.

The world premiere of the film happened at the South by Southwest music and film festival in Austin, TX in March 2012. SxSW has a reputation for being a lively and alternative arts festival, which reflects the anticipated target audience for the film.

The film eventually went on to make $65 million worldwide, $8.5 million of which came from the UK box office. This means that it is not regarded a successful, profitable film.

Key Companies

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) is an American media company, specialising in the production and distribution of film and television. MGM was founded in 1924, and was once Hollywood’s largest and most glamorous film studio. However, following changes in ownership and corporate restructuring, MGM was forced to file for bankruptcy at the end of 2010; putting all of the films that were in production or slated for production under MGM’s management in jeopardy. The most notable casualty was Skyfall (Mendes, 2012). Spyglass Entertainment, a smaller film production studio eventually came to MGM’s rescue. The executives from Spyglass negotiated a deal with Lions Gate Entertainment to distribute on The Cabin in the Woods.

Mutant Enemy Productions is the production company founded by Joss Whedon in 1997 to produce his television show, Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Since these beginnings, Mutant Enemy has become a cross-platform media production company, producing TV (Buffy, Angel, Firefly & Dollhouse in conjunction with 20th Century Fox Television), web content (the very successful Dr. Horrible’s Sing-Along Blog) and film (The Cabin in the Woods).

Lions Gate Entertainment is an American based independent production and distribution company. It is involved in the production of films and the distribution of both films and television. The announcement that Lions Gate would take on The Cabin in the Woods for distribution was made in July 2011.

The ‘Key Creatives’

Drew Goddard (director and co-writer) – Goddard is an American film and television writer, producer and director. He is, perhaps, best known for his collaborations for cross-platform super-creators Joss Whedon (Buffy & Angel) and J.J. Abrams (Alias, Lost, Cloverfield). He has also authored comic books, as part of Whedon’s extended Buffy-verse. The Cabin in the Woods is his first project as director.

Joss Whedon (producer and co-writer) – Whedon is an American screenwriter, film and television producer and director, comic book author, composer and actor. He first gained success being the creator and showrunner for Buffy the Vampire Slayer, before moving into film directing (Serenity [2005]), experimenting with web series, the superhero genre and musicals (Dr. Horrible [2009]). He is of course, currently best known for being the director of Avengers Assemble (2012), which is currently the third highest grossing film of all time. He went from Avengers to shooting a low budget adaptation of Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing, which premiered at the 2012 Toronto International Film Festival.

Many of Whedon’s projects gain cult status, and he has now become regarded as a cross-platform auteur; meaning that his work in all the media forms he works is often recognisable as his. He has several distinctive signatures, including the casting of the same actors across different projects. Whedon’s other tropes are very strong female characters, distinctive dialogue that often includes mainstream and niche pop-culture references and an interest in existential themes.

The Cast

There is no clear protagonist in this film; this is an ensemble cast. The most notable of the performers include:

Bradley Whitford (Hadley) – Whitford is an American stage, TV and film actor, known to audiences for his role in Aaron Sorkin’s long running political drama The West Wing.

Richard Jenkins (Sitterson) – Jenkins is also an American stage, TV and film actor. He gained more fame following his role as Nathaniel Fisher is HBO’s funereal drama Six Feet Under. However he has since appeared in numerous film and television roles including Burn After Reading (2008), Eat Pray Love (2010) and The Rum Diary (2011).

Amy Acker (Lin) – Acker is an American TV and film actress, who is one of the actors who Whedon casts regularly in his projects. She had significant roles in his TV shows Angel and Dollhouse, as well as having more recently appeared in a leading role in his version of Much Ado About Nothing.

Chris Hemsworth (Curt) – Hemsworth is an Australian film and TV actor. Since taking the title role in Thor (2011), he has appeared in a number of high profile mainstream movies, including Avengers Assemble and Snow White and the Huntsman (2012). He is definitely carving himself out the career of a mainstream, Hollywood movie star. The unfortunate delay in the release of The Cabin in the Woods meant that Hemsworth was a much bigger name by the time the film hit theatres. This meant that the distribution campaign could use his name to help appeal to audiences.

Fran Kranz (Marty) – Kranz is an American film, TV and stage actor. His appearance in the film is the second time he has appeared in a Whedon project. He gained fan acceptance as wise-cracking and geeky Topher in Whedon’s last TV show, Dollhouse.

Sigourney Weaver (The Director) – Weaver is an American film actor, who has gained mainstream and cult fame through her role as Ripley in the Alien franchise (Whedon wrote Alien: Resurrection [1997]). She has appeared in many commercial features since her rise to fame in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Her appearance in this film can be described as a cameo, as she is a recognisable face who doesn’t play a role with a lot of screen time. Having an actor of Weaver’s standing on board the project would have helped gain funding and attract an audience.

Audience – Demographic & Psychographic Profile

The primary target audience for this film is quite complex to identify in terms of its demographics.

Age: 20-50. Although the primary target audience for horror is usually 16-24, this film relies on the audience’s familiarity with the genre, particularly classics such as Texas Chainsaw Massacre and The Evil Dead. For this reason, we have to consider the target audience’s age range will be higher, as the film makers rely on the audience having an established knowledge of the genre.

Gender: Male – Even though there will be a clear secondary audience of females, horror’s target audience is typically male – as evidenced by the use of the male gaze and masculine action. Despite the fact that Whedon and Goddard create a more balanced representation of the genders, the film relies on established horror conventions which would target a male audience.

Socio-economic groups: B/C1– This is aimed at a mostly niche audience. Horror is principally aimed at a niche audience, despite its somewhat mainstream values. The niche quality of this film is emphasised by the fact that it is a ‘meta-’ horror; meaning that it is a film about horror films. A more cine-literate, probably with an extended education, would be the demographic groups most likely to engage in the film’s ideological discourse about the audience’s need for horror.

The psychographic profiles of the target audience are likely to be reformers. We can reason that this is the target group, as reformers often reject the mainstream and look for more challenging takes on the conventional. Reformers would also be drawn in by the cult status that Whedon enjoys. In addition, horror genre enthusiasts (of any age, gender, socio-economic demographic or of any psychographic group) are clearly being targeted by this text.

Critical Reviews and Audience Reaction

“This clever meta-horror asks what human need is fed by seeing hot youths get slaughtered, but it forgets to be properly scary.” Peter Bradshaw, The Guardian 12/04/12

“(A) biting satire on the entertainment industry, man’s appetite for violence and older people’s love-hate relationship with youth… If you wanted to be hyper-critical, you could argue Cabin is guilty of the sins that it condemns. It values narrative ingenuity over genuine horror and treats with flippant callousness the characters it slaughters for our gruesome scary-movie delectation.” Chris Tookey, The Daily Mail, 13/04/12

“Cabin is a deliciously devious scare dance that keeps changing the steps until you lose your shit and fall helplessly into its demonic traps. Screenwriters Whedon (Buffy the Vampire Slayer) and Goddard (Cloverfield), in his feature-directing debut, are fright-obsessed. They’re also pissed seeing terror morph into torture porn that drowns the human element in buckets of blood.” Peter Travers, Rolling Stone, 12/04/12

“And if a movie should catch my attention please don’t start it off as any other horror film ever made, it ruins the impression, even though it’s a parody. How would I know this was not just a standard horror movie? With bad acting and a uninteresting plot, not even scary, the only thing that i like about this movie is that its so predictable its funny.” Torbjorn, metacritic.com, 27/08/12

“Horror movies have lost its suspense because we don’t care about the characters and the characters are particularly dumb to make decisions to survive. It makes sense in this film. The actors did a great portraying these clichéd characters…it’s smart and inspired” Mek Torres, imdb.com 05/05/12

What issues do these reviews raise about the film?

The analysis…

The horror genre is clearly signified in studio ident. The title sequence again signals genre using images of blood and the iconography of horror. It also establishes idea of sacrifice and theology. A sharp, jarring juxtaposition is created as the film cuts from the red and black of the title sequence to the blue insert shot of coffee machine with Hadley and Sitterson in the facility. Blue is the binary opposite to red, which makes this cut unexpected. Hadley and Sitterson seem like normal guys – Hadley and his wife want kids – which connotes his hope for the future. There are ambiguous references to Stockholm and Japan. Knowing audience will understand these are references to other countries with a reputation for horror film making. This creates enigma for the audience. Who are these people and what are they doing? They make plans for the future, usually this signals their death in horror films. The two shot connotes how united these two are. Title appears accompanied by a non-diegetic scream. This again, is in complete contrast to the preceding scene. This is unexpected for the audience and suggests the film is going to play with our expectations.

Introduction of the group of kids – Dana is a sexualised (she’s in her underwear) college girl. She is a transgressor ( we learn about an ill-advised affair with her professor). Jules (blonde, but intelligent, pre-med), Kurt (the jock, but also academic) and Holden (who also athletic but bookish) all introduced. These are a variety of characters that conform to varying degrees to the archetypes in the teen horror. We learn that a weekend away is planned, with a hint of a new romance (Holden and Dana). The van is shown with the bike on the back, which is a narrative plant for later. Marty – the stoner – is absolutely archetypal; He is overtly rebellious. Upbeat music is used to aid excitement. The camera stays on the street after the camper leaves. It does this to reveal a FBI/CIA type agent character who reports on their departure. He is not part of the generic conventions of horror. The idea of surveillance, though, suggests that this trip will be unexpected, and creates further enigma for the audience. Marty points at the isolation that they will be experiencing, reninforcing the generic setting where most of the action takes place. These characters need to be in the wilderness, away from possible help.

Cut back to Hadley & Sitterson – the use of cutting on parallel action means the creators are asking the audience to ponder the connection between the kids and these two.

The Harbinger scene – the kids stop at a generically antiquated and desolate gas station for fuel en route. The old gas station setting is reminiscent of Texas Chainsaw Massacre; it’s an intertextual reference. A jump scare is used for Mordecai’s entrance. He’s a horror archetype; rural red-neck stranger with a warning. As is foregrounded later on, the generic conventions dictate that the characters must receive a warning, thus giving them a choice to turn back. The conventions also dictate that the characters must ignore the warning and choose the wrong path. They have free will. Dana, Marty and the gang do exactly that, because that’s what we’ve paid to see.

The journey shots reinforce the rural, isolated location; a generic convention of the horror film. The force field is revealed through the unexpected death of the bird; again creating dramatic irony for the audience. Interestingly, the bird, a bird of prey will initially be read by the audience as a signifier of the horror to come; however, the shock impact with the invisible force field means that this expectation is subverted. The bird is an unknowing victim, who flies blindly into unseen danger. It is, then, a metaphor for our characters. Goddard uses high angle shots makes the characters look powerless.

There is a group shot on arrival at the cabin, which positions Dana as the protagonist. The cabin is as creepy as the audience expects. There is an emphasis on dark wood, stuffed animals, and gruesome pictures. The two way mirror also suggests past voyeurism and establishes the potential romance between Holden and Dana. He is likeable, as he does the right thing on seeing Dana undress through the mirror. The scene is then mirrored when Dana switches rooms with Holden – her watching of him undressing emphasises the idea female gaze and that she finds him attractive.

There is a transition into surveillance gallery which builds on the theme of voyeurism previously established. Hadley and Sitterson are revealed to be the ones watching. They appear to be in control of events at the cabin. But these are likeable characters; the audience may find this intriguing. Aren’t we used to be positioned to dislike the antagonists in horror films?Further enigma is created – what is actually going on? The reference to Jules’ hair dye suggests how this unknown organisation have been creating and controlling them for a while. The Mordecai’s phone call to Hadley on speakerphone subverts the conventional discourse of horror with comedy.

The lake swimming scene establishes the equilibrium for the characters. The diegetic computer screen showing each character gives the impression that they are in some sort of game or experiment and we know they are unknowing participants. This is similar to the tribute tracking screens shown in The Hunger Games (Ross, 2012); a film that explores similar themes. Monitoring their heart rates suggests that their lives are at stake. The betting of the facility staff shows that the employees of this organisation do not value the lives of these people. This is similar to the people in the Capitol betting on the outcome of The Hunger Games.

Hadley & Sitterson talk about ‘the system’, which highlights the generic conventions of the horror film again. The characters have to transgress to be punished. They have free will. They must also be warned about their fate and ignore the warning. They refer to the ‘director’ and to the events as ‘the game’.

Night time. In the party scene there is evidence of the male gaze as the camera focuses on Jules’ rear. This helps to emphasise her sexuality, an idea that is built on further into the scene. The inclusion of the sexualisation of young women, particularly those who are transgressive is common in the horror genre.

The frivolities in the cabin are halted by the cellar door swinging open. Enevitably, predictably, conventionally, the kids go down, unable to resist the temptation. The cellar is full of the iconography of horror, many items are reminiscent of the iconography from iconic horror films. Marty seems to be the only character who is looking at the situation with a sense of the danger they might be in. They each explore different parts of the bric-a-brac cellar, each becoming facinated with a particular prop. Dana is the one that chooses; she draws the group together by chilling reading extracts from the diary of a girl; Patience Buckner. Despite reading a warning out loud, and despite Marty’s protestations, she reads an incantation in latin aloud…

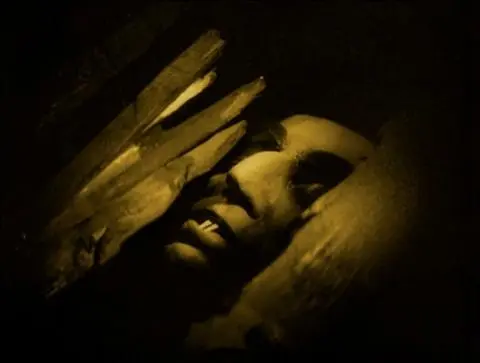

Cut to outside the cabin, in the woods. Low-key lighting is used as the Buckners raise out of the ground. There enterence (bursting up out of their graves is iconic. The music, the lighting and their clear supernatural nature creates an increased sense of threat. It also creates dramatic irony for the audience. We know that monsters are coming for the kids.

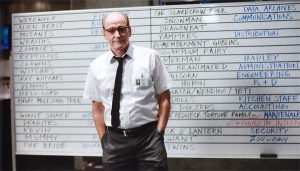

Back at the facility, the assembled workers celebrate and commiserate as the outcome for the betting pool is resolved. The shot of white board suggests the iconic monsters (along with some comedic inclusions – seriously, who’s Kevin?) that the props in the cellar related to. This emphasises the choice the kids have made. They have chosen how they will die. The white board, filled with these choices, is a feature designed with DVD and blu-ray viewing, as these give you the open to pause and to read all the choices clearly. For your convenience, there’s a picture below.

We also have more development on the earlier reference to Japan. We cut to footage where we see a ghost or demon girl in classroom and small school girls, it’s an intertextual reference to J-horror and Korean horror , particularly films like Whispering Corridors, The Ring, The Grudge, Dark Water, etc.

Back at the cabin, we watch as these Kurt and Jules turn into the horror archetypes of the Athlete and the Whore. Holden’s glasses and ability to read latin indicate he is intelligent and educated, he is transforming into the archetype of the Scholar.

Kurt and Jules go out in the woods for some ‘alone’ time. The audience knows that this will be dangerous and our tension levels begin to rise. The diegetic audience of male workers gathered around the big screen in the control room suggests the Mulvey’s idea of male gaze, particularly their reaction to Jules’ reluctance to take off her clothes. Whedon and Goddard use this moment to highlight that part of the pleasure of watching slasher films for a male audience is the objectification of women. Kurt and Jules are transgressing ; sex before marriage is against American, conservative, Christian values. Theorist Carol Clover said that the order that the characters die in slasher films reflects the extent to which they have transgressed against society’s rules. The characters are punished. Jules is killed, as is conventional. A woman dies first, as she is the most transgressive. This links back to ideas about Eve in the Garden of Eden and Original Sin. Kurt is wounded and escapes. Cut to black.

Hadley & Sitterson aren’t happy about the death; this ensures the audience maintain their positive relationship. Enigma is built on again ‘whose slumber’ they talk about. Their words actions seem to suggest this is a sacrifice. What is this mechanical device that we are shown in insert shots? More enigma to be explained later on.

A jump scare is used in Marty’s trip outside; it’s an example of misdirection. We see a Buckner approach, and anticipate her arrival, but Kurt enters from the right of the frame. As we are distracted, this creates the surprise needed for a successful jump scare. Once they are all back in the cabin, and have split up (again, a decision made by Kurt which was influenced by the Hadley & Sitterson) the internal doors are locked. The characters understand this is supernatural, and it is conventional that the haunted house that seems to be controlled by unseen forces is conventional for the genre . We know it isn’t the case here, though; Hadley & Sitterson are controlling it. Marty’s discovery of the camera allows the film makers to point out that the most obvious application of secret cameras to young audience is reality TV. Marty rests against the window, a bad move in any horror film. He is pulled outside by one of the Buckners, presumably to meet his maker.

Kurt, Dana and Holden end up in ‘The Black Room ‘. There is little light in this dark scene. The conventional effect with low key lit scenes in horror films is that we interrogate the frame more; waiting for the threat to emerge from the darkness. Dana’s attack on Judah suggests her transition into what Clover described as ‘The Final Girl’; she was weak, but she is finding the strength and courage to fight back. The audience expects, that if anyone survives, it will be her .

Back in the facility, Hadley says something like ‘It used to be so easy, you’d throw a girl in a volcano” when talking about managing this process. Of course, this is an intertextual reference to King Kong (1933). This reference is a comment on how far the genre has come, and how complex in terms of the variety of experience it offers the audience.

Meanwhile, in Japan, they have defeated the threat this raises the tension for Hadley & Sitterson. However, very quickly another narrative barrier is thrown in their path; Hadley & Sitterson have to stop the kids escaping, which has been complicated as the tunnel has not caved in, as needed. The cutting between the guys in the facility and the kids in the camper van raises an interesting dilemma for the audience: Who are we rooting for? Arguably, if we are there to see a horror film, we will likely find ourselves siding with Hadley & Sitterson, as we still have three characters alive. In horror, that result is not enjoyable for the audience. We want the maximum amount of bloodshed.

Hadley & Sitterson succeed in blocking the exit, which mean that Dana, Kurt and Holden have to overcome this barrier in some other way. Kurt hatches an idea. The bike on the back of the camper is a narrative plant for Kurt’s attempt to escape’ he intents to jump the gap in the road using the bike. There is dramatic irony. We know what will happen, which makes his heartfelt, courageous speech almost comedic. The music builds it into a triumphant moment, which is then subverted by the crash. Holden dies minutes later, ambushed by one of the Buckners. Dana is left alone.

Hadley & Sitterson celebrate. She is the final girl. Their dialogue points to the convention of the character. She doesn’t have to die, but she must suffer. There is a stark juxtaposition between the images of Dana and Judah being displayed on the large screen and the party in the facility. However, their jubilation does not last long, another narrative barrier is highlighted for Hadley & Sittersn; everything hasn’t gone as smoothly as they thought. This information is delivered via a red phone, following a mention of ‘upstairs’ this gives the impression of the importance of the communication and hints at the identity of the caller. We discover that Marty is not dead. This is a twist for the audience, as this information has been withheld.

Dana is rescued by Marty. Together they escape Judah Buckner. Marty reveals where he has been; he got into one of the graves to hide, but instead uncovered an entrance to somewhere incongruous. The gleaming stainless steel of the elevator carriage is another interesting juxtaposition for the audience. However, this type of setting is one we’ve started to associate with Hadley & Sitterson. The moment when the narrative journeys of our two sets of characters will intersect is drawing near. We anticipate it.

Dana and Marty use the lift, not knowing where it will take them. In this sequence, the containment of many, many horrible monsters is revealed. This element of the films feels more like sci-fi than horror. Dana and Marty are revealed to be in a similar containment cell. As the cells shuffle around, Dana spends a moment gazing into the soulful eyes of the ‘deadite’ (an intertextual reference to the cenobites in the Hellraiser franchise) who is holding his puzzle globe. She realises the choice that she made.

They arrive in the facility, and defeat the first guard using the help of a severed Buckner hand. This brings some comedic relief. Dana and Marty cautiously make their way out into the lobby.

A voice in the facility addresses Dana and Marty over a PA gives confirmation of the sacrifice and talks of placating the ‘ancient ones. The voice is recognisable; Signorney Weaver. Her status as an actress means that the audience will understand that she is likely the Director that has been mentioned previously. Taking refuge in the security booth, Dana releases all the monsters.

The final battle is nothing short of a blood bath. Dana’s choice to release the monsters instead of submitting to her fate is an act of rebellion against the system (again another connection with the actions of the protagonist in The Hunger Games). This sequence is a comment on the ridiculousness of contemporary ‘gore porn’ where the emphasis is on showing the audience a lot of gore and disturbing scenes of horrible things happening to characters we aren’t invested in, instead of creating tension and fear for what may happen to characters we do care about. Throughout the film, the audience considers the identity of the real antagonist in this scenario. Is it Hadley & Sitterson, The monsters? The director? The ancient ones? Hadley & Sitterson both die; Hadley poetically, comedically the victim of a merman attack. Sitterson’s death is more tragic. It comes at Dana’s hands. With his last breath, Sitterson implores Dana to kill Marty to complete the ritual and save the world.

Dana and Marty end up a ritual chamber, they see the images of the horror archetypes carved into the wall; the whore, the athlete, the scholar, the fool and the virgin. The director arrives to try to convince them to complete the ritual; she says that the Ancient Ones will rise if the rite is not completed. This will bring the end of the world. The room begins to rumble from below, suggesting the ‘Ancient Ones’ are already stirring. Dana contemplates killing Marty but decides against it. There is a physical confrontation between Marty and The Director. Marty is saved, though, as Patience Buckner (who has wondered back down through the facility) takes out The Director. Both Patience and The Director plummet over the edge of the platform and into the abyss. Dana and Marty survive, and presented in a two shot, connoting their unity at this point, share a joint as the world ends. They accept the need for there to be something different, something new. Their drug taking connotes their rebellion against the system; their refusal to be part of the ritual which will punish them for their youth. The film ends with a massive hand rising up out of the ground below the cabin and grabbing the camera. Cut to black. Roll credits.

Of course, this film leaves some unanswered questions for the audience to ponder on. Who are the Ancient Ones? Perhaps they are The Devil and other creatures from theology that represent evil for the cultures that speak of them? One of the most popular ideas is that the film is a cinematic metaphor for horror films themselves. If this is the case, then who are the Ancient Ones really? Are they us? The cinema audience that likes to watch horror. If we accept that, then the film suggests that watching simulated human suffering has a purpose. What happens if we do not have an outlet to exorcise the darker side of the human psyche? The end of the film suggests that the genre needs a reinvention; perhaps things have become too predictable. Are Hadley & Sitterson basically substitutes for the writers Whedon and Goddard? They are two middle aged men, who’s job it is to deliver to the director what the audience will enjoy, to figure out how to engineer the right characters and situations, and to include the important genre ingredients. Are the other workers just a metaphor for a film’s crew? Maybe. The film does seem to suggest that contemporary horror has become too extreme and has sacrificed tension and character development for graphic and disturbing suffering. Maybe Dana and Marty are right. Maybe it is time for a change.